1 Introduction

The Crow Canyon Archaeological Center initiated the Northern Chaco Outliers Project (NCOP) in 2016 (Ryan 2016), and fieldwork began in earnest in 2017 (Simon et al. 2017). The NCOP’s main purpose is to study the Lakeview Community, which is a collection of four neighboring Chaco period Great Houses located in southwestern Colorado. The four Great Houses are subsumed by three archaeological sites: the Haynie site (5MT1905), Ida Jean (5MT4126), and Wallace Ruin (5MT6970).

Excavations at the Haynie site (5MT1905) have comprised the vast majority of NCOP-related fieldwork over the last six years. Haynie is a complex, multicomponent ancestral Pueblo archaeological site intermittently occupied between roughly A.D. 800 and 1175 (Throgmorton et al. 2022, 2023). It includes two Great Houses, a large Pueblo I-II roomblock, and numerous other structures and contexts dating to the Pueblo I and II time periods.

Examining archaeofaunal remains from the Haynie site is one important part of the Northern Chaco Outliers Project. In the first year of archaeofuanal analysis, Dombrosky and Gilmore (2023) reported three different findings worth summarizing here. First, the Haynie fauna has a low rate of identifiability associated with a high amount of fragmentation. Preliminary predictive models indicated that thick cortical bone (from medium mammals and larger) fragments are highly associated with unidentifiabiltiy. However, those preliminary models did not take into account whether unidentifiable remains are associated with disturbed contexts, which is a conspicuous feature of the Haynie site. Second, identification rate estimates suggested that new identification types were still quickly added as we progressed through the analysis. Those results indicated that our estimations of taxonomic diversity were still incomplete, but that the Haynie site was still likely not notable in terms of taxonomic diversity compared to other sites in the central Mesa Verde region. Finally, the first year of archaeofaunal analysis also focused on two different rare taxa recovered from the Haynie site: wolf (Canis lupus) and bison (Bison bison). We developed a highly accurate model used to classify wolf, coyote (Canis latrans), fox (Urocyon spp. and Vulpes spp.), and domesticated dog (Canis familiaris) from mandibular measurements using a massive reference database provided by Welker et al. (2021). The model we developed was 100% confident in identifying the mandible specimen from Haynie as wolf. Additionally, we illustrated how we identified bison remains and discussed the clear importance of medium-to-large game procurement at the site.

In this report, we revisit and expand some of these previous topics all while reporting on a year’s worth of new identifications. In the identification section (Section 3), we repeat some of the information presented before, but have provided a new subsection that focuses on summarizing the contexts that dogs (genus Canis) have been recovered from in the central Mesa Verde region and how the Haynie site compares. The new section called Taxonomic Abundance by Study Unit (Section 4.1) works to identify excavation contexts that are most likely disturbed, and the taphonomy section (Section 4) incorporates this new information into a new model to tease apart factors driving unidentifiablity. Finally, we re-estimate identification rates at the site to gauge taxonomic representativeness and compare these estimates to all of the faunal assemblages in the Crow Canyon database. Our larger goal is to document the quality of zooarchaeological data produced from May 2023 to August 2023; we firmly believe that a focus on data quality is essential to valid archaeological interpretation. Data quality underlies almost every facet of archaeological research.

2 Materials and Methods

There are three analysts associated with the data described here: Jonathan Dombrosky, Eric Gilmore, and Ahna Feldstein. Jonathan Dombrosky has approximately 12 years of experience with archaeofaunal analysis, and he analyzed new specimens associated with this report from May 2022 to August 2023. Eric Gilmore had approximately 3 years of experience with archaeofaunal analysis, and he analyzed specimens as a Crow Canyon Zooarchaeology Intern in the summer of 2022. Ahna Feldstein has 4 years of experience with faunal analysis and was a Crow Canyon Zooarchaeology Intern from May 2023 to July 2023. Jonathan, Eric, and Ahna are respectively referred to as Analyst 1, Analyst 2, and Analyst 3 in all subsequent interanalyst comparisons.

The main comparative collection used for the analysis of the Haynie site archaeofauna is housed in Crow Canyon Archaeological Center’s Laboratory. Three cottontail (Sylvilagus spp.) specimens and one black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus) specimen were loaned from the Laboratory of Zooarchaeology at the University of North Texas. We took specimens that were difficult-to-identify to the Museum of Southwestern Biology’s Division of Mammals and Division of Birds located in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Various osteological guides, manuals, atlases, and keys aided identification. Several publications assisted with the identification of mammal remains (Adams and Crabtree 2012; Chavez 2008; Gilbert 1980; Hillson 1986, 1996; Jacobson 2003; Olsen 1964; Smart 2009). Bird remains were identified with other works (Cohen and Serjeantson 1996; Gilbert et al. 1981; Hargrave and Emslie 1979; Olsen 1979), as well as fish, amphibian, and reptile bones (Olsen 1964). Some consulted references helped identify both avian and mammalian remains (Broughton and Miller 2016; Elbroch 2006). Yet other works verified nonhuman from human remains (Baker et al. 2005; France 2009; White et al. 2012).

We followed identification protocols explicitly designed to enhance data quality (Driver 1992, 2011; Wolverton 2013; Wolverton and Nagaoka 2018), and used the coding system by Driver (2006). Briefly, analysts adopted a conservative approach to identifying zooarchaeological specimens at the Haynie site. It is an almost impossible task for analysts to understand how all diagnostic skeletal criteria change through time, among species, within different age classes, between sex, and across geographic areas on a fragment-by-fragment basis. It has been argued that identifications become less taxonomically specific when analysts have more experience, greater access to diverse comparative materials, and a specific focus on data quality (Gobalet 2001; Lyman 2002, 2019; Wolverton and Nagaoka 2018). This lack of taxonomic specificity likely increases identification accuracy in situations where assemblages contain an abundance of fragmented remains from closely related taxa.

We use the Number of Identified Specimens (NISP) to report taxonomic abundance, and this quantitative unit is a tally of all archaeofaunal specimens within a given taxonomic classification. NISP is the most basic quantitative unit from which most others are derived, such as the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI). NISP is preferred because it is often highly correlated with measures like MNI. It is also devoid of errors in additive calculation that plague minimum number units (Grayson 1984; Lyman 2008). We also rely on a non-standard unit called Unique Identification Types (UITs) to estimate taxonomic diversity (Section 5). In the last report, we called this unit the Number of Unique Identifications (NUIDs). The way this unit is calculated is exactly the same. We have simply changed the name after conversations with colleagues.

All statistical analyses and figures were produced with R version 4.3.1 (R Core Team 2023). Our statistical analyses are structured with tidyverse packages and syntax (Wickham et al. 2019). All graphs were produced with ggplot2 (Wickham 2010). We built predictive taxonomic and taphonomic models using a supervised learning workflow (Hastie et al. 2009; James et al. 2013; Kuhn and Johnson 2013); this included using the tidymodels metapackage to split our data and implement basic model features (Kuhn and Silge 2022). We rely on logistic regression and random forest as the engines for our predictive models. Logistic regression is a powerful modeling engine designed for binary classification (Kuhn and Johnson 2013, 282). Random forest models predict classes based on one or more variables through a large assortment (a forest) of small decision trees (Kuhn and Johnson 2013, 198). Random forest models sometimes outperform more traditional predictive models (Cole et al. 2022).

3 Identified Taxa

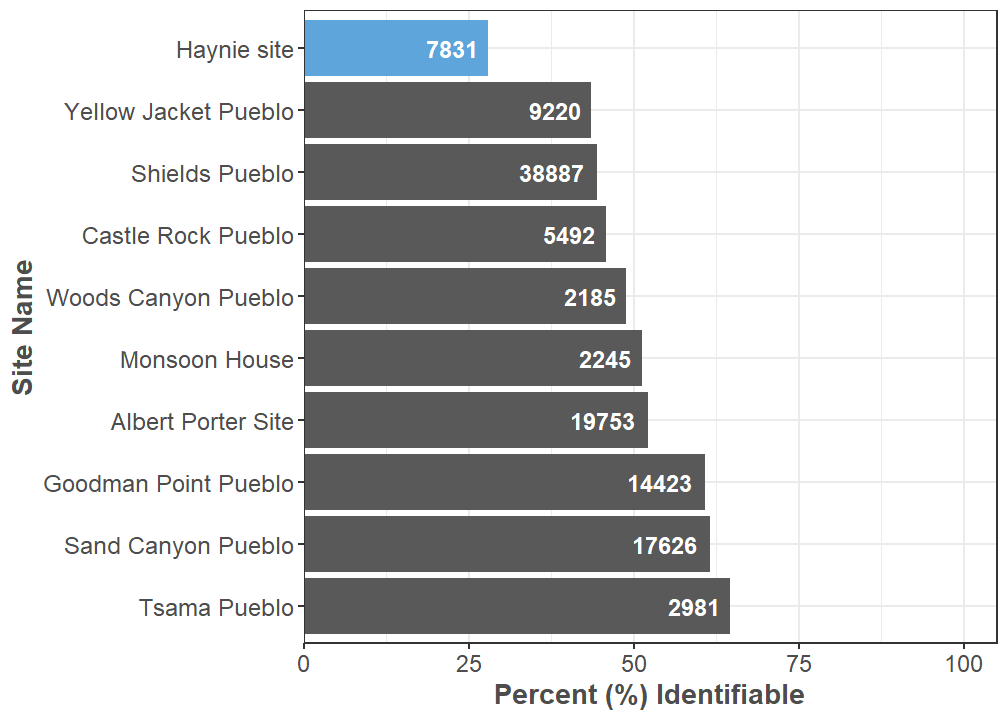

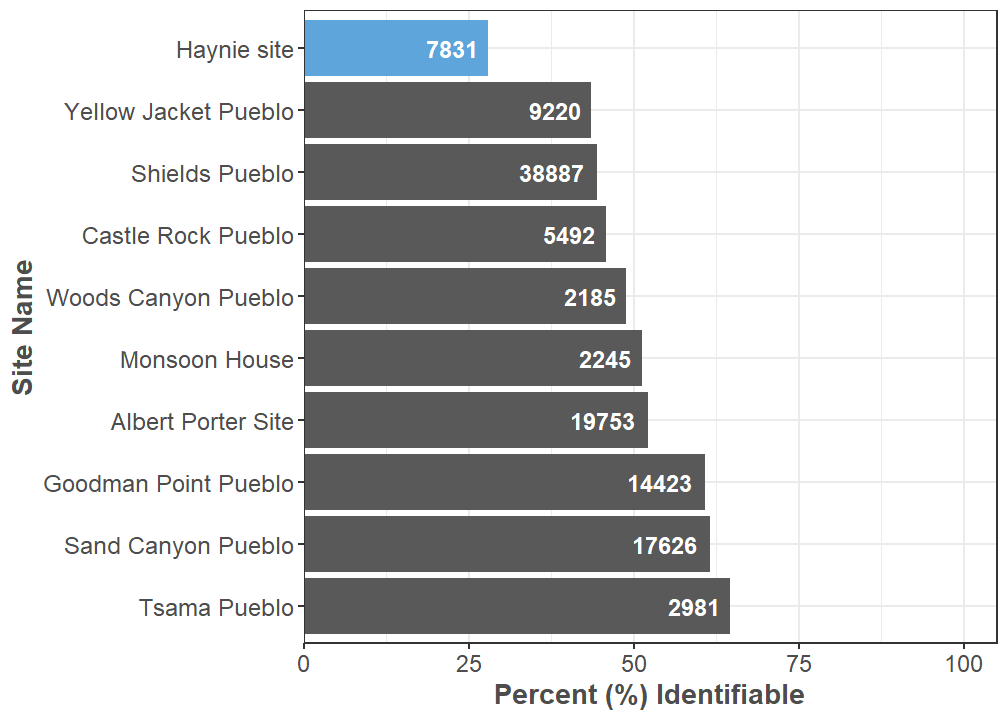

There are 2191 identifiable and 5640 unidentifiable specimens so far in the Haynie archaeofaunal assemblage. We have added 590 identifiable and 1359 unidentifiable specimens—for a total of 1949 specimens—since our last report. Our identification rate is still low at 27.98%, which has practically gone unchanged. Of all of the large faunal assemblages that Crow Canyon has analyzed over the years, Haynie currently has the lowest identification rate (Figure 1). Analyst 1 analyzed 62.47% of the assemblage, Analyst 2 analyzed 20.6%, and Analyst 3 analyzed 16.93%. There are 4 classes of animals present: Mammalia (mammals), Aves (birds), Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes), and Reptilia (reptiles). There are 4 orders of mammals present, 7 orders of birds, 1 order of ray-finned fishes, and 1 order of reptile. In total, we used 61 identification types (Figure 2).

3.1 Mammalia (n = 1964)

3.1.1 Lagomorpha (n = 761)

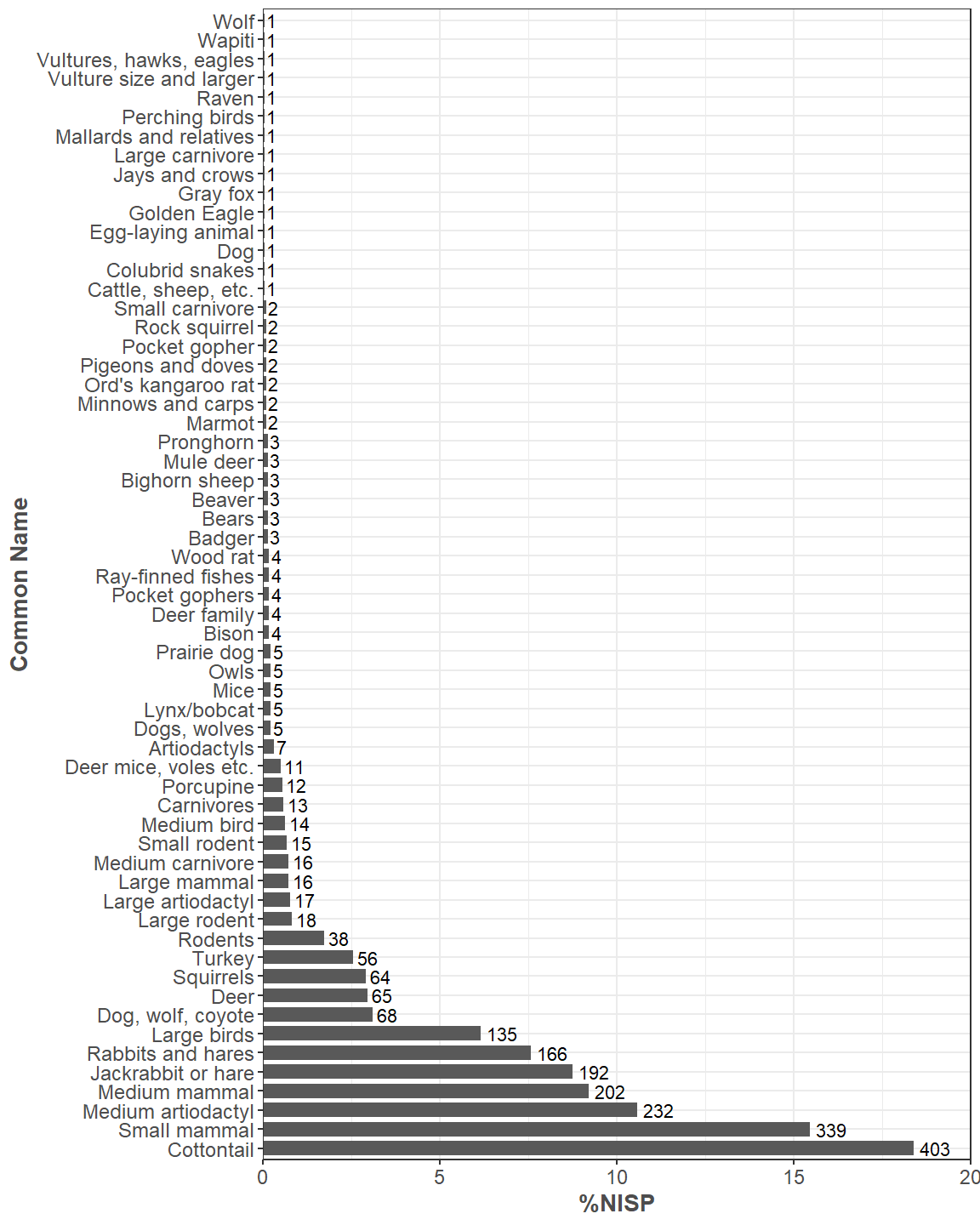

Cottontails (Sylvilagus spp.) and jackrabbits (Lepus spp.) are the main taxa in the order Lagomorpha at the Haynie site. Lagomorphs are currently the most abundant animals identified, comprising 34.73% of the identified specimens. It has been hypothesized that populations of larger-bodied jackrabbits decreased through time in the central Mesa Verde region, and that this decrease is likely due to human overhunting (Driver 2002; Ellyson 2014). Thus, the ratio of cottontails to jackrabbits—commonly referred to as the Lagomorph Index—is a basic quantitative unit of general interest in the area, and in western North America in general (Driver and Woiderski 2008). The Lagomorph Index at the Haynie site is 0.68, which indicates a fairly equal relationship between the abundance of cottontails and jackrabbits. Haynie currently has the lowest Lagomorph Index of all the large (greater than 1000 NISP), central Mesa Verde faunal assemblages in the Crow Canyon database (Figure 3). This number is similar to the Lagomorph Index from some Pueblo II components of Shields Pueblo (5MT3807). Shields serves as an important point of comparison—here and in subsequent analyses—considering that it and Haynie both have similar site features (i.e., Great Houses) and general occupation histories (Rawlings 2006).

Garden hunting is an important subsistence practice to consider at the Haynie site, and the moderate Lagomorph Index value is also interesting in this regard. Researchers argue that higher ratios of cottontails to jackrabbits indicates a higher reliance on garden hunting in the central Mesa Verde region (Driver 2011). What could the more even relationship of cottontail and jackrabbit abundance indicate about garden hunting at the Haynie site? Future work using stable isotope analysis (sensu Dombrosky et al. 2023) might help shed light on whether garden hunting was prevalent at the site, and it also might help describe the relationship between the Lagomorph Index and garden hunting in general.

3.1.2 Small Mammal (n = 339)

This identification group includes those mammals jackrabbit size and smaller. This non-standard identification includes all small mammal specimens lacking morphological features required for more specific taxonomic levels. Consequentially, it has a high likelihood of incorporating many lagomorph specimens since they are exceedingly abundant in southwestern archaeofaunas. This identification group will be incorporated into final comparisons of size-based abundance indices through time, between areas of the Haynie site, or between sites. The goal will be to gauge the impact this identification group has on final interpretations of the Lagomorph Index.

3.1.3 Artiodactyla (n = 340)

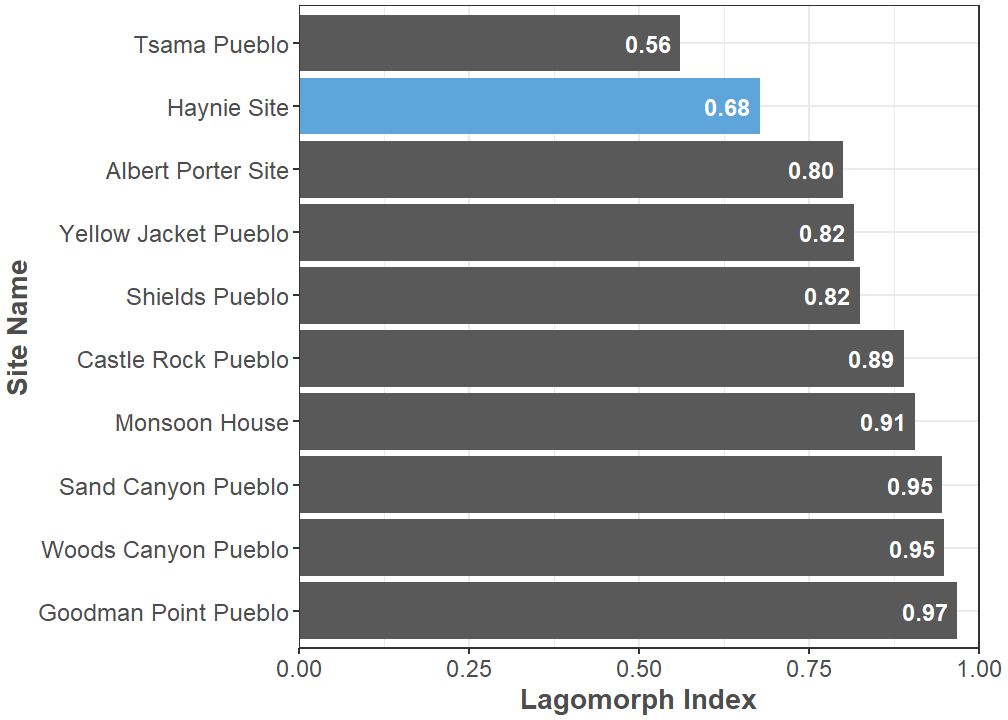

Even-toed hoofed animals make up the order Artiodactyla, and they are currently 15.52% of identified specimens at Haynie. Substantial zooarchaeological evidence indicates artiodactyls—mostly mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), and bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis)—were severely overhunted in the central Mesa Verde region (Badenhorst and Driver 2009). Some models suggest that deer populations might have been so low that any observable deer was immediately hunted after A.D. 1000 (Bocinsky et al. 2012). For this reason, the Artiodactyl Index is another basic quantitative unit of general interest in the region and in the larger northern U.S. Southwest. It measures the ratio of large-bodied artiodactyls to small-bodied lagomorphs in an archaeofaunal assemblage (Broughton et al. 2011). The current Artiodactyl Index at Haynie is 0.31. This value may seem somewhat low, but in reality it is quite high. The Haynie site has the highest Artiodactyl Index of all the large (exceeding 1000 NISP) faunal assemblages in the Crow Canyon Research Database, the only exception is a Pueblo IV site from the Northern Rio Grande called Tsama Pueblo (Figure 4).

Large artiodactyls—elk (Cervus canadensis) and bison (Bison bison)—are also notable parts of the Haynie archaeofaunal assemblage. These specimens comprise 6.47% of artiodactyls. There are currently 4 bison specimens, and Dombrosky and Gilmore (2023) reported on these specimens in detail. Importantly, these specimens do not overlap with each other and represent an MNI of 1.

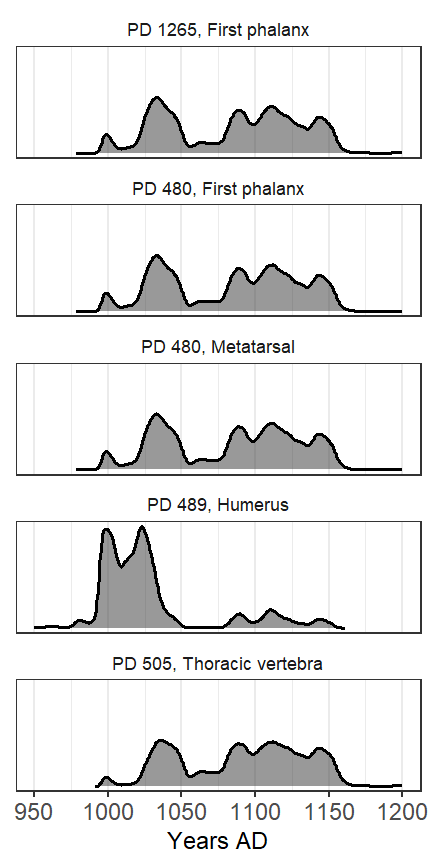

We radiocarbon dated five bison specimens to help determine whether more than one bison individual is present at the Haynie site (Figure 5). Four specimens were found in somewhat similar upper layers of a trench (PDs 480, 489, and 505). One specimens (PD 1265) was found in lower layers of this trench within a feature. The conventional radiocarbon age and error of the specimen from the lower feature is identical to two specimens from the upper layers, while two separate specimens from these upper levels have somewhat different calibrated ages. Altogether, there is almost complete overlap in the 95% calibrated date ranges. Radiocarbon dating has not confirmed whether there are separate individuals or not, but what is apparent is that either deposition occurred rapidly in this general area of the site or that stratigraphic mixing is more pernicious than originally anticipated.

3.1.4 Medium Mammal (n = 202)

Mammals larger than a jackrabbit and up to deer size are considered medium mammals. There is a high probability this identification group incorporates many artiodactyl specimens since they are one of the most common medium mammals in southwestern archaeofaunas. It should be incorporated in sensitivity analyses that rigorously assess final conclusions relying on size-based abundance index values, such as the Artiodactyl Index.

3.1.5 Rodentia (n = 187)

Rodents are 8.53% of identified specimens, which is a small component of the overall assemblage. The ratio of sciurids to rodents can help gauge the impact of intrusive species. Members of the squirrel family (Sciuridae) are notorious intruders of archaeological deposits, especially prairie dogs (Cynomys spp.). The majority of prairie dog skeletal fragments are identified to the family level, as it is extremely difficult to skeletally distinguish prairie dogs from ground squirrels. This means that the Sciuridae identification has the highest potential for accumulating prairie dog specimens. And, indeed, we can confirm that the vast majority of sciurid specimens compare favorably to prairie dogs. Sciurids make up 39.04% (n = 73) of the rodent assemblage. Given that rodents comprise a small portion of the overall assemblage, it does not appear that rodent intrusions pose a significant problem for interpretation at the site. We will, however, closely track the taxonomic composition of rodents as the Northern Chaco Outliers project progresses. Importantly, rodents could have been actively hunted (Badenhorst et al. 2023). One way to disentangle intrusive from non-intrusive rodents is through radiocarbon dating (Guiry et al. 2021). This could prove useful if prairie dog specimens preclude clear interpretation of the Haynie archaeofaunal assemblage in the future.

Large rodents, those larger than a woodrat (Neotoma spp.), comprise 18.72% of the total rodents currently identified. Beaver (Castor canadensis) and porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) specimens are the most notable. Beavers prefer aquatic habitats while porcupines take refuge in trees along active floodplains (Baker and Hill 2003; Roze and Ilse 2003). The presence of these species might suggest hunting activities that were focused in riparian habitat close to the site.

3.1.6 Carnivora (n = 119)

Carnivores are a small portion of currently identified specimens at the Haynie site (5.43%), but a number of canid specimens were discussed in detail in last year’s report (Dombrosky and Gilmore 2023). There are currently 76 specimens from the family Canidae in the Haynie site fauna. Many of the specimens come from an articulated domestic dog offering and one specimen is a wolf mandible. We provide a contextual analysis of Canis spp. deposition across all Crow Canyon projects considering the importance of this group of animals to the Northern Chaco Outliers Project.

3.1.6.1 Spatial Context of Canis spp. Specimens

Domestic dogs and their wild counterparts filled many roles within the Ancestral Pueblo world; dogs were used for companionship, raw materials, subsistence, and in ritual practices such as dedicatory offerings in burials, and artistic depictions (Monagle and Jones 2020). Recent investigations from Arroyo Hondo Pueblo suggest that, contrary to our modern interpretations of domestication, no such dichotomy existed between domestic and wild canids in Pueblo society (Monagle et al. 2018). Coyotes and dogs often swapped or shared roles within their communities, and both species were included in instances of ritual deposition (Monagle et al. 2018).

It is clear that canid remains offer great insight into past human lifeways (Semanko and Ramos 2022), and they hold an especially important space within the cultural landscape of the central Mesa Verde region. Aside from the turkey (Meleagris spp.), dogs are commonly cited as the only domesticated animal within this region prior to Spanish colonization. Ethnographic research on historic and modern Pueblo communities suggests that canids fulfilled specific roles as protectors, warriors, companions, hunting assistants, spirits, messengers, pests, trash-eaters, food, witches, and sometimes even substitutes for humans (Monagle and Jones 2020). The time-depth and spatial patterning of canine deposition is highly diverse in this region (Hill 2000). The Haynie faunal assemblage contains specimens attributed to domestic dogs, coyotes (Canis latrans), and wolves (Canis lupus), meaning that human-canid relationships are especially complex at this site.

For estimating the relative abundance of canid specimens at Haynie, NISP was chosen as our basic unit of analysis. As an additive measurement of taxonomic abundance, NISP avoids those issues of aggregation which often accompany derived units such as MNI (Minimum Number of Individuals). NISP and MNI nonetheless often share a strong correlation which may be examined to address issues of fragmentation and interdependence (Grayson and Frey 2004).

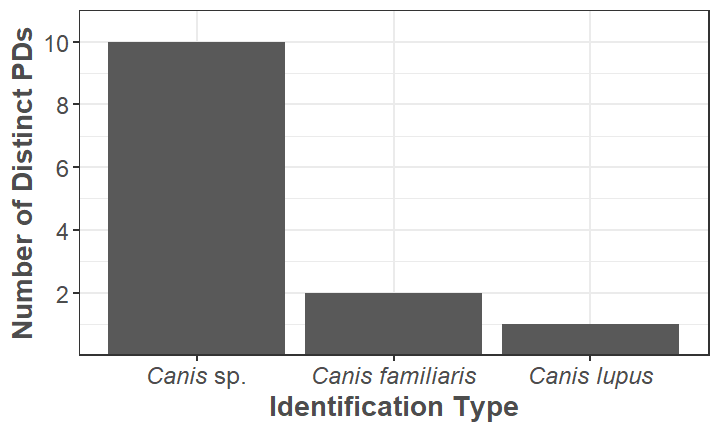

There are currently 70 specimens from the genus Canis in the Haynie archaeofaunal assemblage. The genus Canis includes domestic dogs, coyotes, and wolves. Taxonomic classification beyond the genus level is notoriously difficult based on post-cranial morphology, but select specimens from Haynie have been identified to the species level. Taxonomic identifications based on unique Provenience Designation (PD) are represented by Figure 7.

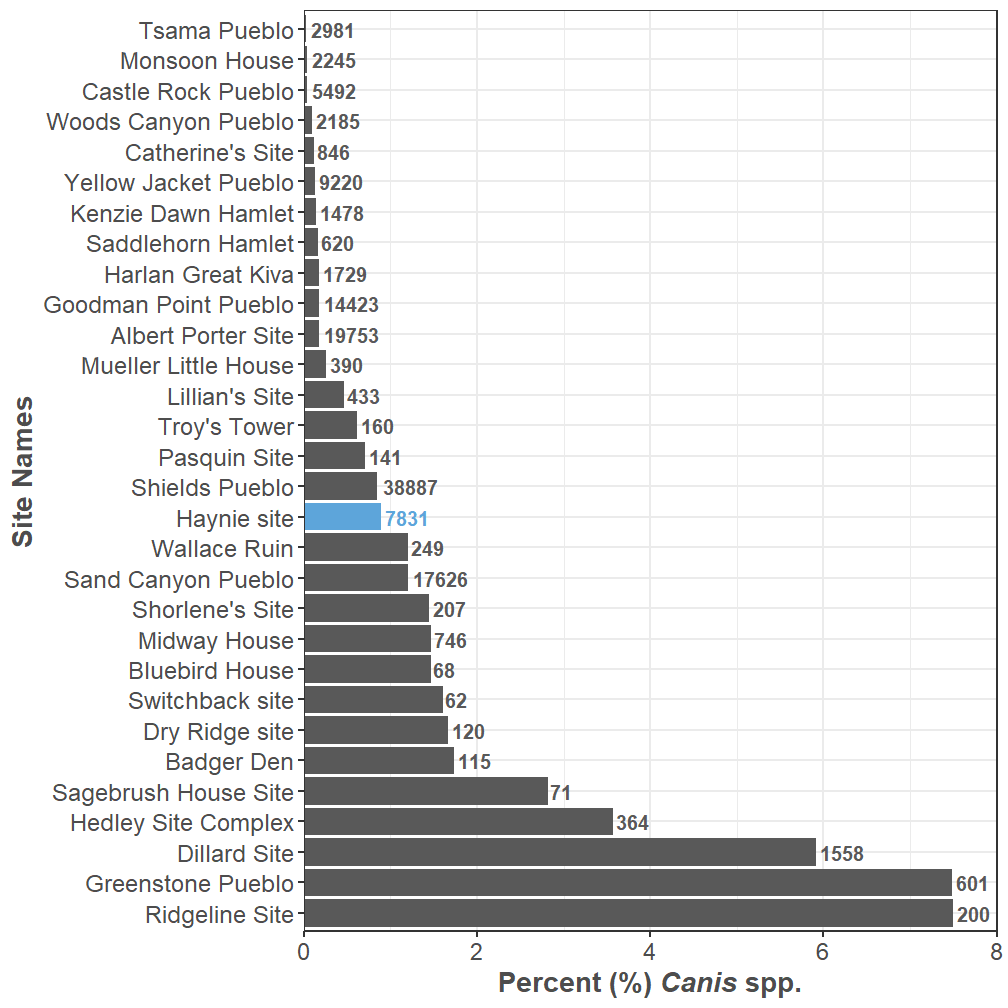

Canid specimens are relatively rare across the entire Crow Canyon archaeofaunal database, contributing less than 8% of total NISP at all sites (Figure 6). Canid remains at the Haynie site comprise a mere 0.89% to the total raw NISP of 7831. Given the established role of dogs, coyotes, and wolves within Pueblo society, the overall scarcity of canine remains indicates a selective process of canine deposition.

An initial spatial analysis of canine deposition at Haynie helps untangle the complex relationship between humans and dogs within Ancestral Pueblo society. By observing the abundance and spatial distribution of their remains, we begin to understand key associations between canine individuals and the built environment. A canid’s transition from life to death is preserved in its deposition, allowing us to glean information on how these individuals were felt, seen, and treated by their human counterparts. Continued contextual analysis of canid remains offers greater potential to understand how the Haynie site may adhere to or diverge from local trends of animal management within the broader Mesa Verde region.

To evaluate the spatial distribution of canid remains, we first pursue analysis based on provenience designations (PD) for each specimen at Haynie. According to the Crow Canyon Field Manual (Center (2001)), an artifact’s PD is assigned based on its mode of deposition and stratigraphic position.

The Haynie assemblage contains two important instances of canid deposition from the first year of archaeofaunal analysis (Dombrosky and Gilmore 2023). The first specimen, a wolf mandible, was recovered from the fill between two floors of a surface room (Throgmorton et al. 2022). The mandible from year one is currently the only specimen identified to Canis lupus (see Figure 7), confirmed through the application of predictive modeling with mandible biometrics.

The second set of specimens belong to a single individual, likely a small domestic dog. 56 of the total 70 canine specimens at Haynie belong to this domestic dog, all sharing one distinct PD. The dog’s upper half was uncovered from the floor of a pitstructure, and its lower half was deposited outside of the unit (Throgmorton et al. 2022).

During this year’s archaeofaunal analysis at Haynie, another domestic dog mandible was added to the database. The mandible was identified to Canis familiaris based upon mandibular body width, small overall size, and lack of elongation compared to coyote, wolf, and fox (Vulpes vulpes).

Specimens classified as Canis spp. are designated to the genus Canis, but cannot be identified to domestic dog, coyote, or wolf based on morphological characteristics. Specimens in this category may originate from any of the aforementioned Canis species. Coyote remains are likely represented by the Canis spp. category, though no specimens from Haynie have currently been identified to Canis latrans.

To begin to examine depositional trends at Haynie, we employ descriptive categories established by Erica Hill to understand general trends across all sites within the Crow Canyon faunal database. The three main descriptive categories of canid deposition include ceremonial trash, dedicatory offering, and simple interment (Hill 2000). For this analysis, we apply the term deposition as opposed to interment to avoid assumptions of intentionality. We also change ceremonial trash to ceremonial discard in the following analysis, in adherence with historic and current Pueblo perspectives. We suggest the future use of ceremonial discard as opposed to Hill’s original terminology, the problematic nature of which is discussed below.

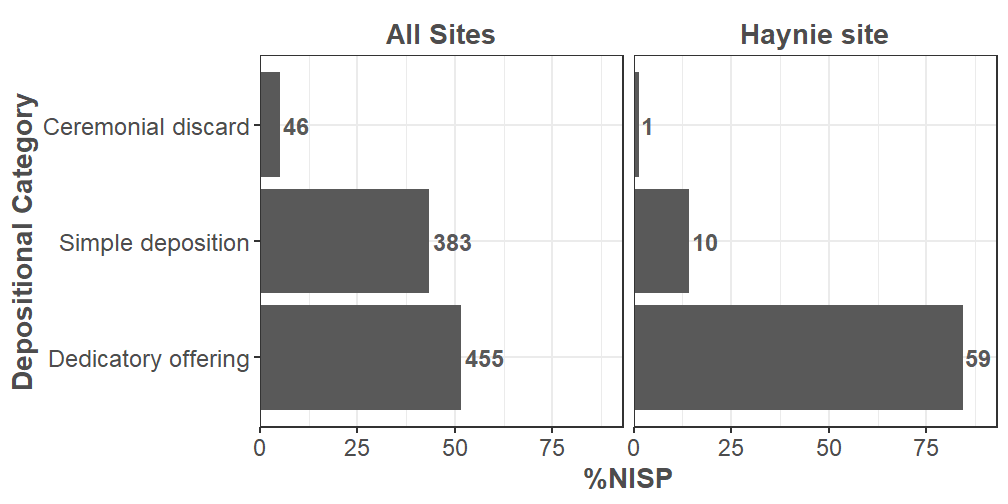

Dedicatory offerings dominate, with the highest NISP counts coming from surface burials (Figure 8). However, specimen interdependence is driving this trend: the articulated remains of a single dog comprise the majority of identified canid specimens at Haynie (Throgmorton et al. 2022; Dombrosky and Gilmore 2023). The small dog’s remains contribute to an inflated NISP count and MNI of 1. Greater overall NISP counts within surface burials may not, therefore, suggest the presence of more dogs; but instead the careful deposition and preservation of select individuals.

The domestic dog’s skeletal articulation and placement adhere to the key characteristics of dedicatory offerings, as outlined by Hill (2000). Dedicatory offerings feature deposition within ritual spaces, often representing the ceremonial closure of architectural features such as kivas. Similar deposition practices have been observed at sites within Mancos Canyon (Monagle and Jones 2020), and from Basketmaker III/Pueblo I period sites in Dolores, Colorado (Hill 2000), illuminating a broader pattern of ritual deposition across the Mesa Verde region.

The deposition of a singular domestic dog mandible in midden reflects our expectations for ceremonial discard. Ceremonial discard involves the ritual dispatch of an individual and their subsequent burial outside habitation areas, usually in a sacred space or shrine. Hill (2000) states that dogs suspected of witchcraft may appear as ceremonial trash. Midden deposits are often regarded as sacred spaces in Pueblo communities (Fladd et al. 2021), and the deposition of objects within middens is considered an important rite-of-passage between the lived and spiritual worlds (Walker and Berryman 2023). This mandible is the most recently-identified domestic dog specimen, and the lone example of ceremonial discard in the Haynie assemblage.

Hill’s descriptive categories offer an avenue for distinguishing patterns within a complex system of human-animal interaction. To gauge how Haynie compares to other sites within the Mesa Verde region, the relative abundance of canid remains per depositional category is assessed across the entire Crow Canyon database (Figure 9).

Across all sites in the database dedicatory offerings are most abundant, followed closely by simple deposition. Simple deposition denotes instances of canid deposition lacking the characteristics of both ceremonial discard and dedicatory offerings. Remains within this category may indicate expedient disposal, focused on the discard of sick or burdensome canines (Hill 2000). Simple deposition may also contain particular forms of deposition which involve ritual behavior, but do not adhere to Hill’s classifications (Hill 2000).

NISP values for dedicatory offerings and simple deposition do not differ substantially, though instances of ceremonial discard remain scarce. Less than 2% of canid specimens across all sites fall into the category of ceremonial discard (Figure 9). Limited occurrences of ceremonial discard may imply the limited deposition of canine remains in middens, or their use in depositions outside the scope of Hill’s categories. The wolf mandible deposited between two floors is included in simple deposition, and is further discussed below.

Despite small sample size, depositional trends at the Haynie site generally align with those maintained across all sites in the Crow Canyon archaeofaunal database. Overall, dedicatory offerings are most abundant, followed by simple deposition and ceremonial discard. Unlike at Haynie, where NISP values for dedicatory offerings are significantly inflated and contribute less than 75% to the overall sample, no one type of deposition dominates across the entire Crow Canyon database (Figure 9).

It is possible that some instances of canid deposition cannot be classified, or have been inappropriately classified according to the aforementioned three categories. Given the sheer volume and diversity of canine specimens in the Crow Canyon database, it is necessary to address the potential pitfalls of Hill’s interpretive approach. Some zooarchaeological research calls into question the breadth and scope of Hill’s descriptive frameworks. Monagle and Jones (2020) applied these categories to an analysis of Puebloan canid deposition, and found the archaeological data are contradicted by ethnographic accounts which blur the lines between ceremonial trash and dedicatory offerings.

Hill (2000) suggests that dedicatory offerings are differentiated from ceremonial trash based upon the function of the individual in death; dogs who have been ritually dispatched and deposited of as ceremonial trash serve no further role beyond that which they play in life, whereas dogs interred as dedicatory offerings continue to function as social and spiritual actors in death (Hill 2000). On the other hand, Pueblo groups consider discard a integral stage in the life of an object, welcoming its transition from one role in society to the next (Fladd et al. 2021; Walker and Berryman 2023). Hopi people, for instance, place particular emphasis on the intentional retirement of objects with important personal or ancestral connections (Walker and Berryman 2023).

The wolf mandible recovered in year one of archaeofaunal analysis (Dombrosky and Gilmore 2023) represents one such intersection between ceremonial discard and dedicatory offerings. The specimen is classified as simple deposition according to Figure 9, despite its recovery from surface room fill. The mandible cannot be classified as an element of ceremonial discard nor dedicatory offering according to Hill’s classification criteria (Hill 2000). The specimen nonetheless represents an intriguing instance of canid deposition. The wolf’s mandible may illustrate a specialized process of deposition by its very presence.

Pueblo ideas of canid deposition, both current and historic, offer an important avenue for unraveling the nature of human-canid interaction at Haynie. Moving forward, it is crucial to address the problematic nature of the term “trash” when discussing animal deposition in Pueblo society, as this terminology suggests a sense of indifference toward discarded materials following their deposition (Walker and Berryman 2023). The deposition of canid remains in midden deposits can reflect a range of personal and collective choices, enacted as a way to express, preserve, and commemorate key aspects of the living community (Fladd et al. 2021). We have therefore chosen to employ the term “ceremonial discard” in this analysis, and suggest that this term replace original terminology introduced by Hill (2000) to characterize discard in midden deposits.

Given these perspectives, it is apparent that dog deposition at the Haynie site is highly complex; colored by a vast and nuanced system of human-canid interaction. The application of frameworks such as Erica Hill’s (Hill 2000), which employ general descriptive categories, are useful for broader understandings of canine life in Pueblo society. For future analysis, it is crucial that Indigenous perspectives are prioritized as the primary interpretive framework for understanding canine life in the Mesa Verde region.

3.1.7 Large Mammal (n = 16)

The large mammal identification includes mammals larger than deer, and it includes specimens lacking morphological features required for more specific taxonomic levels. It is likely that it could incorporate large artiodactyls like elk and bison specimens. It should be incorporated in sensitivity analyses that rigorously assess conclusions based on these animals.

3.2 Aves (n = 219)

3.2.1 Large Birds (n = 135)

Birds larger than a mallard are considered large birds. This identification group is most likely dominated by Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) as they are one of the most frequent birds recovered from ancestral Pueblo sites. A high proportion of Turkey specimens are assigned to this group considering that there is considerable skeletal morphological overlap between Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis) and Turkey (Hargrave and Emslie 1979). The Crow Canyon comparative collection does not, as of yet, include Sandhill Crane skeletal material. As a result, this group is frequently used as it represents a conservative identificaiton.

3.2.2 Galliformes (n = 56)

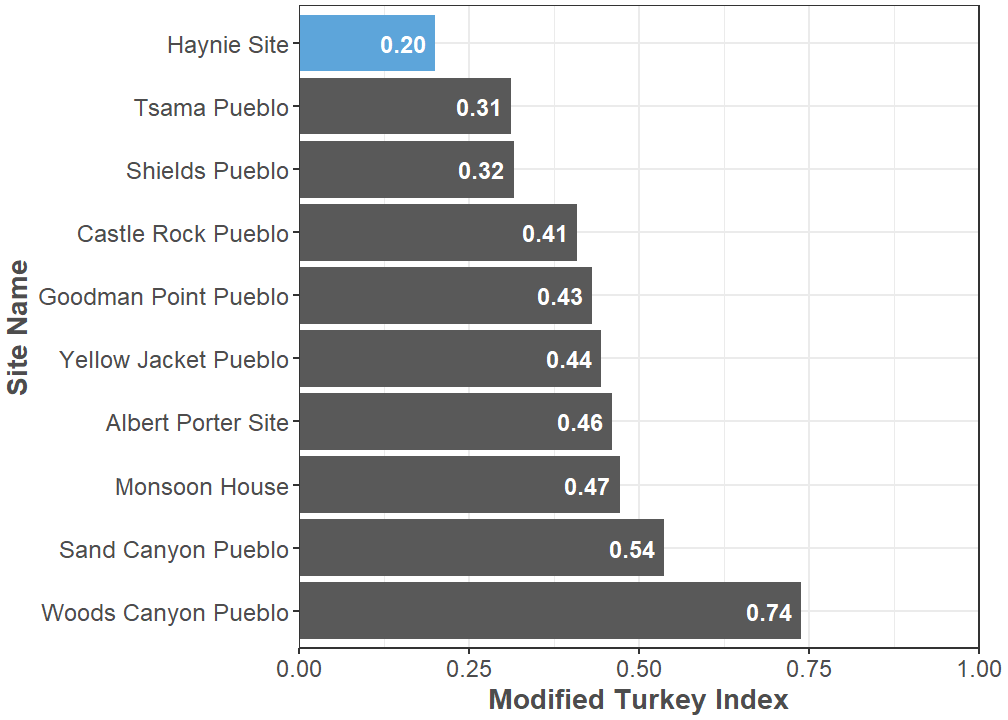

All Galliformes specimens identified so far in the Haynie assemblage are Turkey, but it is still surprising how few Turkey specimens there seem to be. For instance, Spielmann and Angstadt-Leto (1996) proposed the Turkey Index, which is the ratio of Turkeys to lagomorphs in an assemblage. The current Turkey Index for Haynie is 0.07, which is notably low. However, Driver (2002) proposed the Modified Turkey Index where the large bird identification group is included in the calculation. The current Modified Turkey Index value for Haynie is 0.20. This value is within the normal range for Pueblo I/Pueblo II sites in the central Mesa Verde region (Badenhorst and Driver 2009), but it is the lowest Modified Turkey Index for large assemblages in the Crow Canyon Research Database (Figure 10). Also worth noting, there appears to be an abundance of turkey specimens yet to be identified. It is doubtful that this low index value will remain constant as the faunal sample increases. How Turkey husbandry was managed at the community-level is an essential future area of research for the Northern Chaco Outliers Project. This line of inquiry is one way to delve deeper into aspects of cooperation and identity at the Lakeview Community.

3.2.3 Medium Birds (n = 14)

Medium birds are considered larger than a robin and the size of a mallard or smaller. It is difficult to attribute the majority of this identification group to a single taxon, as it contains a variety of difficult-to-identify fragmented skeletal parts that could belong to numerous taxa.

3.2.4 Strigiformes (n = 5)

The owl specimens identified at the Haynie site are a terminal phalanx, second phalanx, first phalanx, femur, and ulna. Owl feathers are known to have been incorporated into dance paraphernalia and prayer sticks (Ladd 1963). It is, however, important to keep in mind that owls can be active taphonomic agents. Luckily, their signatures are well-known and include the presence of pellets, small mammal remains with little to no fragmentation, and visible signs of digestion on specimens (Andrews and Cook 1990; Fernández-Jalvo and Andrews 2016). Owls do not appear to be a taphonomic agent of concern at Haynie (Section 4).

3.2.5 Passeriformes (n = 3)

Three passeriform specimens have been identified so far in the Haynie assemblage: one small fragmented humerus generally identified to the order-level, a tibia fragment identified to Corvidae (the family comprising jays and crows), and one large carpometacarpus identified as Raven (Corvus corax).

3.2.6 Columbiformes (n = 2)

Pigeons and doves are in the order Columbiformes, and one ulna fragment and one sternum fragment were recovered from Haynie. These specimens are most likely a Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura). An order-level identification was used because the Crow Canyon comparative collection does not include a Band-tailed Pigeon (Columba fasciata), which is the only other member in the order Columbiformes to consider in the region.

3.2.7 Accipitriformes (n = 3)

Two specimens were identified as general members of the order Accipitriformes: one general foot phalanx and one terminal phalanx that compared favorably to a Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura). The other specimen was a distal tibiotarsus fragment identified to Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). This specimen was taken to the Museum of Southwestern Biology’s Division of Birds and identified with their skeletal comparative collection. It was distinguished from Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) based off the morphology of the supratendinal bridge, which is more convex and more proximally robust in Golden Eagles compared to Bald Eagles. Eagles are acutely significant in Pueblo culture and their feathers are extremely valued (Beaglehole 1936; LaZar and Dombrosky 2022; Tyler 1991).

3.2.8 Anseriformes (n = 1)

One complete carpometacarpus was identified to the genus Anas spp. (mallards and other relatives) from the Haynie site. While this specimen could likely represent the common mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), Hargrave (1965) mentions the likely presence of Mexican Duck (Anas diazi) in the Four Corners region in the past. He based this assertion on the recovery of Mexican Duck feathers associated with Tusayan Polychrome sherds from Glen Canyon. The presence of different mallards and ducks is of potential biogeographic significance and the different members of this genus represent difficult-to-separate taxa.

3.3 Actinopterygii (n = 6)

This taxonomic class includes the ray-finned fishes. Six specimens have been identified to this general class: two ribs and three fragmented vertebrae centra (of which two of these specimens can be identified to the order-level, see below). Following Nelson (2006, 35), fish specimens should no longer be referred to as pisces, as it is an antiquated taxonomic term. Similarly, for fishes of inland North America, the use of osteichthyes should no longer be used (Nelson 2006, 83). This is so for two interrelated reasons. First, this term has been replaced by the Euteleostoma designation. It successfully describes a monophyletic clade that includes tetrapods. Secondly, since Euteloestoma includes tetrapods, it includes lobe-finned fishes (Sarcopterygii). Lobe-finned fishes—like the coelacanth (Actinistia)—are not native fishes in inland North America during the late Holocene (Cloutier and Forey 1991). The use of osteichthyes should be accordingly abandoned. Instead, Actinoptergygii (ray-finned fishes) should be used because it is a more accurate class-level designation for archaeofaunas from the U.S. Southwest/Mexican Northwest.

3.3.1 Cypriniformes (n = 2)

This order includes carps, minnows, and suckers, which are common fishes in the aridland streams of the U.S. Southwest (Minckley and Marsh 2009; Sublette et al. 1990). These two specimens are small intact vertebrae. The lateral ridge morphology of centra can be used to identify vertebrae of fishes from U.S. Southwestern archaeofaunas to the order-level. Common orders of fishes found in rivers in the U.S. Southwest include Cypriniformes, Siluriformes, Lepisosteiformes, and Salmoniformes, and each of these orders have distinct vertebral morphology. These specimens are also notably small. It is possible inhabitants of the Haynie site used non-targeted methods to capture fishes, such as seining (Dombrosky et al. 2022). A focus on fishing practices offers a basic way to understand aquatic habitat use associated with the Simon Draw watershed.

3.4 Reptilia (n = 1)

3.4.1 Squamata (n = 1)

One colubrid (family Colubridae) vertebra was identified from Haynie. This specimen was identified to the family-level using Olsen (1964). It likely represents a bullsnake (Pituophis catenifer sayi), which is one of the most common colubrids in Cortez, CO.

3.5 Oviparous Animal (n = 1)

Eggshell specimens were identified as oviparous animal. These specimens are likely from Turkey, but a general identification was given because a scanning electron microscope could not be used to assess mammillary cone morphology (Beacham and Durand 2007; Conrad et al. 2016; Lapham et al. 2016). It is possible, though unlikely, that this eggshell could be from a lizard.

4 Taphonomy

The most important taphonomic question surrounding the Haynie archaeofauna is: what is causing such a high degree of unidentifiability (Figure 1)? Last year, we posed the hypothesis that the high unidentifiability rate might be related to a high degree of artiodactyl exploitation (Dombrosky and Gilmore 2023). It could be that Haynie site occupants not only obtained a larger than average amount of artiodactyls (Figure 4), but that they intensively and extensively processed artiodactyl skeletal elements for within-bone nutrients as well (sensu Wolverton 2002). Haynie site occupants might have caused the high unidentifiability rate through their subsistence practices.

To support this hypothesis, we created a predictive model to test whether or not combinations of taphonomic variables could predict identifiable or unidentifiable specimens. Using logistic regression, we could confidently predict whether specimens were unidentifiable. The model we created indicated that one of the most important variables in predicting unidentifiability was whether a specimen had thick cortical bone. Considering that long bone shaft fragments have the highest incidence of thick cortical bone in our sample, we reasoned that these specimens are most likely linked to the most abundant medium-sized mammals recovered from the Haynie site (i.e., artiodactyls).

However, a crucial variable was left out of the predictive model we created: whether or not specimens come from areas of recent disturbance. This variable is crucial because the Haynie site exhibits extensive evidence for recently disturbed deposits, whether it be through mechanical disturbance, looter’s pits, or yard modification (Throgmorton et al. 2022, 2023). Unidentifiability could be linked to a high degree of artiodactyl fragmentation caused by recent disturbance. Here, we explore the relationship between unidentifiability through simple data visualization and hypothesis testing, we then add a new disturbance variable to the logistic regression model we developed last year. We also go a step further and compare our results to a different model type called random forest. This helps answer an additional question: could we develop more predictive accuracy—and clearer variable importance estimations—from using different model engines?

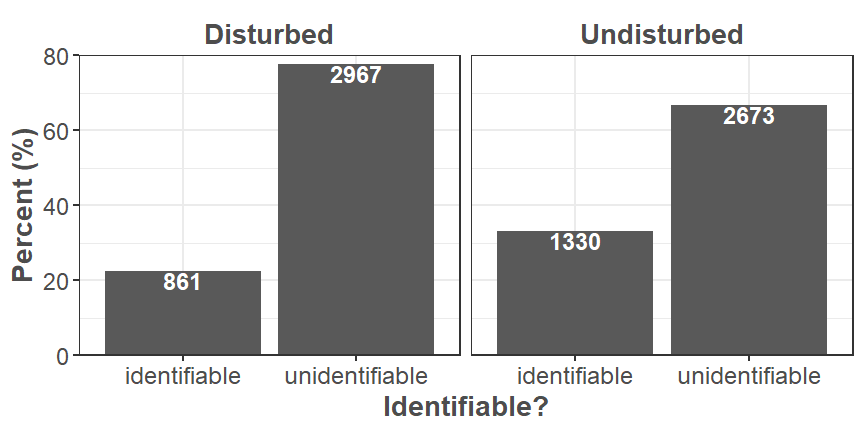

4.1 Identifiability by Recently Disturbed Contexts

There is a surprisingly similar ratio of unidentifiable to identifiable specimens from across disturbance contexts at Haynie given that almost half of the analyzed specimens are from contexts of recent disturbance (Figure 11). Approximately 78% of the specimens from recently disturbed contexts are unidentifiable, and about 67% of the specimens from undisturbed contexts are unidentifiable. Is this 11% difference significant given the sample sizes in each category? To test this question, we conducted a Pearson’s chi-square test of independence. It appears there is an association between identifiability and disturbance context (χ2 = 111.86, p < 0.01), with a low effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.12).

Inspecting the residuals (the difference between expected and observed counts) reveals an interesting pattern. There are larger residuals for the number of identifiable specimens in both disturbed and undisturbed contexts, while there are smaller residuals for unidentifiable specimens in each context (Figure 12). This suggests that unidentifiable specimens do not deviate from expected counts in each of the disturbance contexts.

Given the large sample size and the inspection of residuals, the association between identifiability and disturbance contexts is of very little practical significance. There is a non-random association, but it is of little magnitude or weight (see Wolverton et al. 2016). These results indicate that recently disturbed contexts will likely have little influence on predicting whether specimens are unidentifiable.

4.2 Updated Taphonomic Model

4.2.1 The Penalized Logistic Regression Model

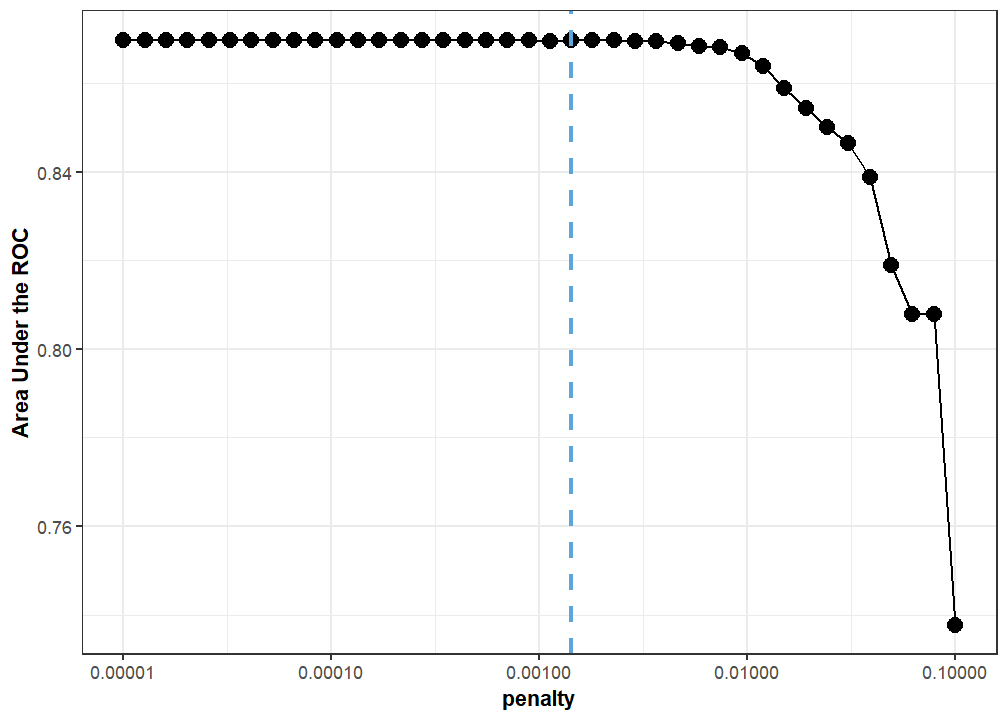

Similar to last year, we randomly split our data into a training and test set, which comprises 80% and 20% of the data respectively. Our validation set consists of 80% of the data from the training set. This year, we stratified our training, test, and validation sets so that equal portions of identifiable and unidentifiable specimens are within each group. We compare penalized logistic regression and random forest models to predict unidentifiable specimens from this year’s sample. Dombrosky and Gilmore (2023) details the logic of creating a predictive model to understand taphonomic variable importance, we do not provide further justification here. The models are supplied with 17 predictor variables for every specimen: if it 1) came from an area of recent disturbance, if it had 2) thick cortical bone, 3) excavation damage, 4) carnivore damage, 5) at least one intact end, 6) a spiral fracture, 7) a transverse fracture, 8) an irregular break, if it was 9) a shaft fragment, 10) made into an artifact, 11) eroded, 12) gnawed by rodents, 13) splintered, 14) root etched, 15) burned, 16) who the analyst was, and 17) its maximum length.

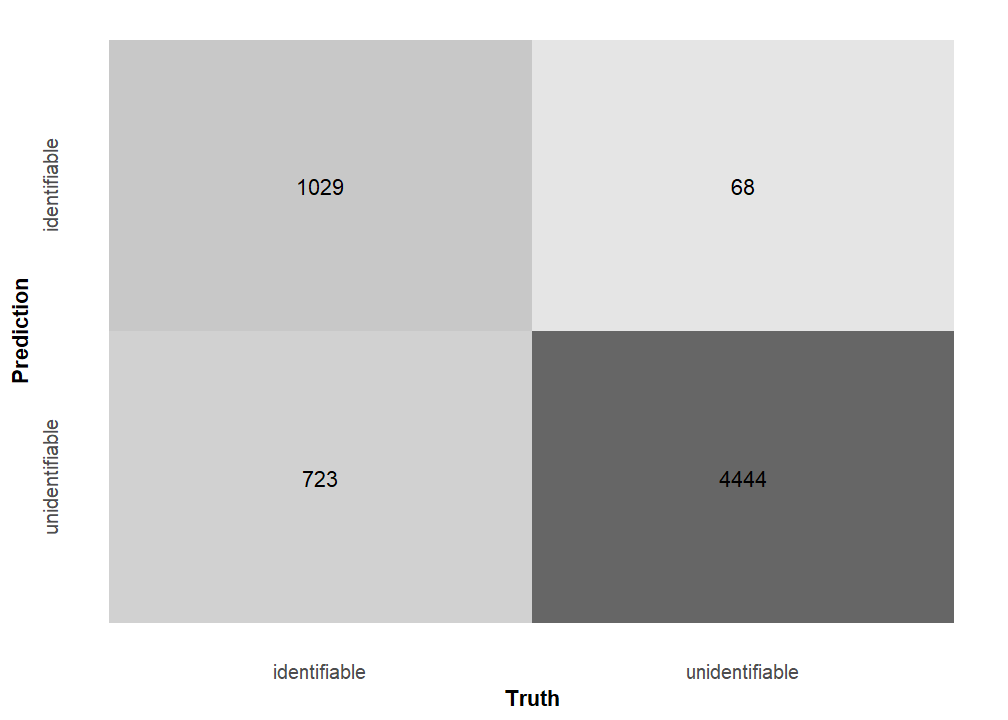

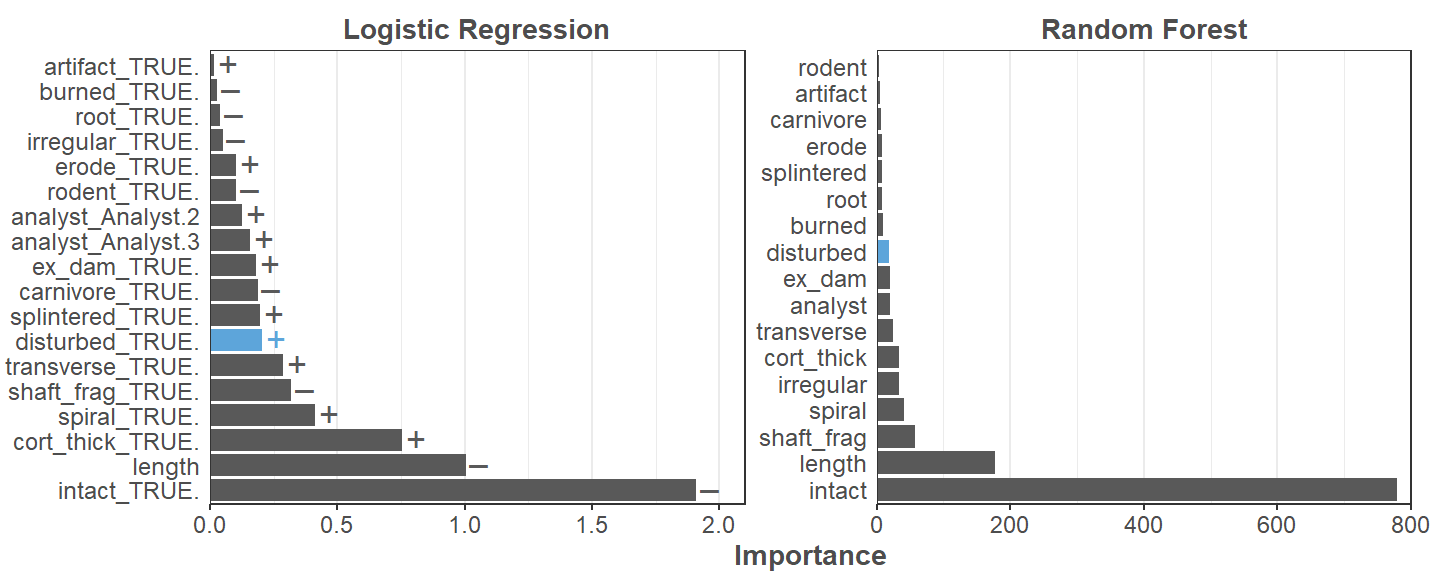

The penalty term in the logistic regression model safeguards against highly correlated predictor variables, which can cause poor model performance. We used grid search on the validation set to tune 40 candidate penalty values, and we picked the one with the highest area under the Receiver Operator Curve (ROC) for our final model (Figure 13). The subsequent model was 87.37% accurate on the training set. Like last year, there was a large discrepancy between two other accuracy metrics. The Matthews correlation coefficient for the trained model is 0.68 while its F1 metric is 0.92. The F1 metric is markedly higher—indicating a model with high performance—because it describes how an event of interest is predicted. In this case, the event of interest is how well the model predicts unidentifiable specimens rather than identifiable ones (Figure 14). The model’s accuracy on our test set is remarkably similar, at 87.36%. As such, the logistic regression model fulfills the purpose of this analysis.

4.2.2 Random Forest Comparison

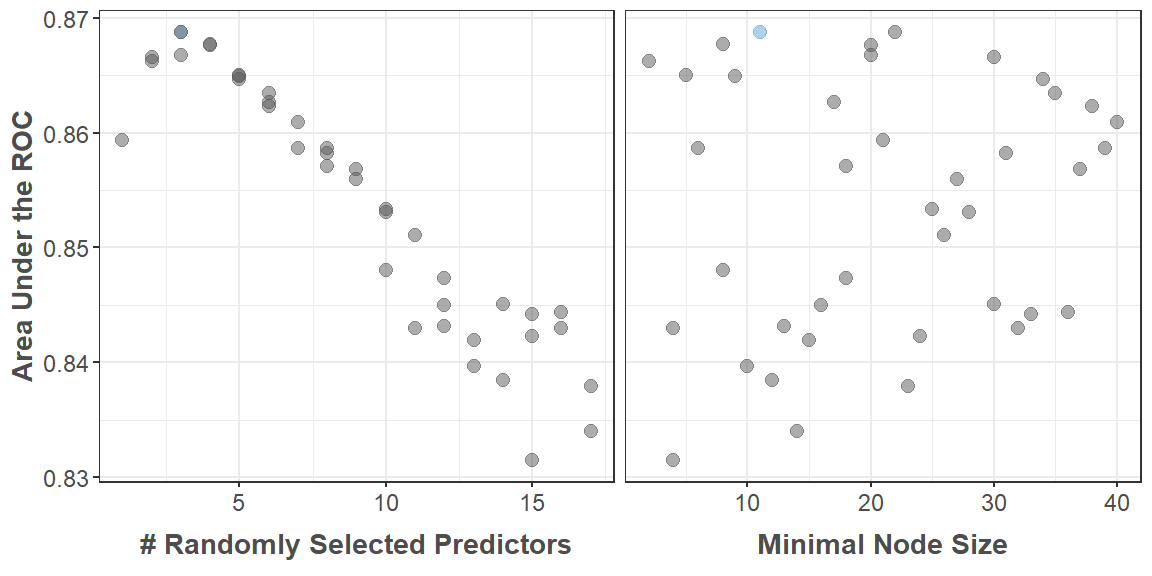

Though the penalized regression model is generally high performing, it is possible that other predictive model types could provide higher accuracy and performance in different ways. We compare the logistic regression model to a random forest. Random forest models sometimes perform better than logistic regression models as the number of predictor variables increase in a dataset (Kirasich et al. 2018). Our model consists of a number of variables of unknown quality for prediction (i.e., noise versus explanatory variables), which underscores the need for optimal tuning parameters and model performance comparisons.

We tune two parameters in our random forest model: number of predictors randomly sampled at each tree and the minimum number of data points in a node required for further splitting. Parameters were selected using the highest area under the ROC (Figure 15). The tuned random forest model is 87.79% accurate on the training set, and there is a large discrepancy between the Mathews correlation coefficient (0.69) and F1 metric (0.92). These classification metrics for the trained random forest model are almost identical to those from logistic regression. And, indeed, the results are almost identical when comparing the two models’ performance on the test set (Figure 16). The random forest model does not increase or decrease predictive accuracy when compared to the logistic regression model.

The random forest model does, however, provide a different view of variable importance, because it uses a series of drastically different steps to predict whether a specimen is unidentifiable or not (Figure 17). Disturbance context is the 7th most important variable in the logistic regression model. The two most important variables, which detract from unidentifiability, are whether or not a specimen has one intact end and the specimen’s length. The two most important variables adding to unidentifiability are whether the specimen has thick cortical bone or whether the specimen has a spiral fracture. For the random forest model, disturbance context is the 10th most important variable. The top three most important variables are whether or not there is an intact end, the length of the specimen, and/or whether it is a shaft fragment.

The most important variable across both models is whether or not a specimen has at least one intact end. The more intact a specimen is the more identifiable it is. We believe this result is a sign of high data quality. An assemblage with high identifiability on specimens lacking morphologically distinct features (i.e., intact ends) would be alarming.

Our new models further support the hypothesis that medium-to-large mammal fragmentation is a key taphonomic feature of this assemblage. However, the above results also indicate that disturbance context does not heavily influence unidentifiability. We believe artiodactyl exploitation mixed with intensive and extensive within bone nutrient processing could be the cause of the high unidentifiability rate.

High numbers of artiodactyl specimens relative to other staple hunted animals (lagomorphs) paired with high fragmentation pose a potential conundrum. On one hand, these specimens could indicate efficient foraging practices, where Haynie hunters were able to consistently acquire high-ranked prey. On the other hand, foraging efficiency could have been low since large game were so thoroughly processed. The calculation of fragmentation rates per skeletal part and across the skeleton of individual artiodactyls will help resolve this issue (sensu Wolverton 2002). Understanding these patterns through time will be especially important to consider. Future effort should be focused on assessing whether artiodactyl fragmentation increases through time or if the amount of fragmentation remains stable through Haynie’s occupational sequence. It could be that culinary practices were thorough—requiring high levels of processing—and remained stable through time.

This future analysis will also help address a glaring and basic issue: is fragmentation artificially inflating NISP values, obscuring the relatively high artiodactyl index at Haynie? Next year’s report will focus explicitly on this issue. We will calculate the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI), Minimum Number of Elements (MNE), %whole, and NISP:MNE at Haynie and across sites in the Crow Canyon Research Database.

5 Taxonomic Diversity and Representative Sampling

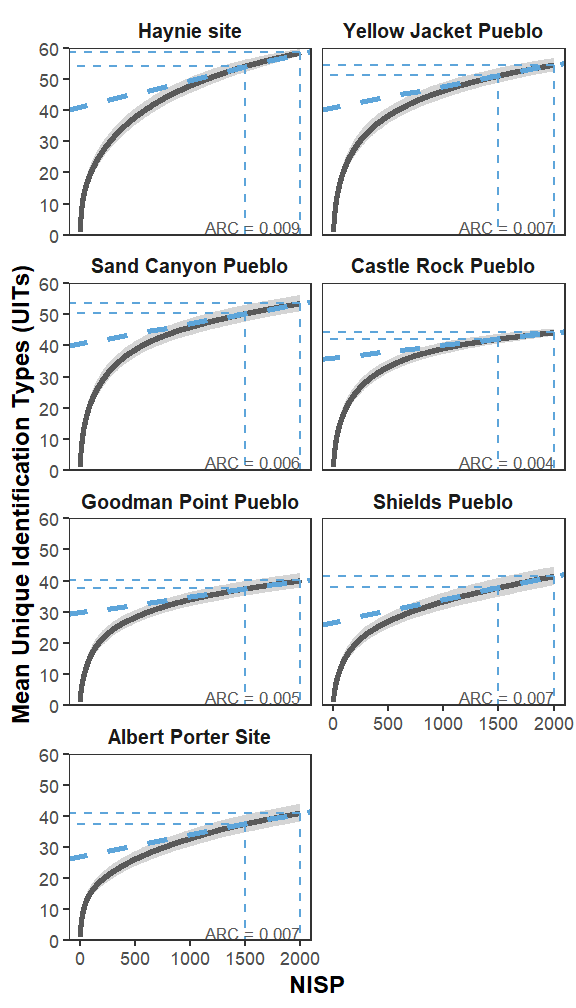

Last year, we wanted to understand whether or not Haynie had a more diverse fauna compared to other sites. The Lakeview Community is located in a natural corridor (Simon Draw) that could have facilitated the movement of both birds and large game, supplying highly diverse wild resources to Haynie site residents. We compared rarefaction curves across three other archaeological sites to test this hypothesis (Shields Pueblo, Sand Canyon Pueblo, and Ponsipa’akeri). Rarefaction curves allow us to compare taxonomic diversity across multiple sites (while controlling for sample size) and to assess whether sampling efforts have been sufficient enough to provide accurate taxonomic representation. In our initial analysis we found that Haynie was not remarkably diverse and that sampling still was not suffecient enough to provide an accurate estimation of taxonomic diversity. Here, we update the rarefaction curves with sites across the entire Crow Canyon Research Database that exceed 2000 NISP.

This analysis relies on a non-standard quantitative unit to estimate taxonomic richness called Unique Identifications Types (UITs). It is a tally of the different identification types present in a specific context, meaning it can include standard taxonomic identifications (e.g., Odocoileus sp.) and non-standard identifications (e.g., medium artiodactyl). This unit serves as a proxy for taxonomic richness to help gauge patterns in sampling and recovery. We prefer this unit over the common Number of Taxa (NTAXA) for three reasons: 1) it is simpler to calculate when dealing with large mixed assemblages identified to a variety of taxonomic levels, 2) it does not require the selection of an arbitrary taxonomic group from which to aggregate all lower units within, and 3) it is strongly correlated with NTAXA when calculated at multiple levels of taxonomic resolution (Dombrosky and Gilmore 2023, fig. 18).

Taxonomic diversity accumulates fastest within the Haynie site fauna compared to six other large assemblages from the central Mesa Verde region (Figure 18). However, we do not yet consider the rate of accumulation significantly different enough to argue that species diversity at Haynie is somehow anomalous. One new identification type is added every 116 NISP at Haynie, while the other sites usually add a new identification type about every 162 NISP. Future work will focus on factoring in the duration of site occupation at each site (sensu Varien and Potter 1997; Varien and Mills 1997; Varien and Ortman 2005). Controlling for site occupation and increasing sample size will clarify these patterns. Additionally, we view analyzing 116 identifiable specimens for every new identification type low sampling effort. Based on these findings, we also conclude that sampling effort has not yet been sufficient enough to accurately capture all of the taxonomic diversity at Haynie. The final word on taxonomic diversity will have to wait until we analyze more specimens. If the rate of change continues its upward trajectory, and does not level-off, Haynie may indeed be interpreted as anomalously diverse faunal assemblage in the central Mesa Verde region.

6 Conclusion

Archaeofaunal analysis at the Haynie site continues to point to new and exciting areas of research. Inter- and intrasite analysis of canid deposition reveals a complex system of human-canine interaction at Haynie and across the central Mesa Verde region, challenging conventional conceptualizations of domestication. Further analysis will consider canine age profiles and associations with non-canid taxa, painting a more vivid picture of canine-human relationality in Ancestral Pueblo society. Haynie also currently has one of the highest artiodactyl index values in the region, and some of the lowest lagomorph and turkey indices. Taphonomic analysis continues to suggest that high numbers of artiodactyls and the processing of their skeletal parts is a primary cause of the high unidentifiability rate at the site, even when recently disturbed contexts are considered. Next year’s report will explicitly include an in-depth analysis of fragmentation patterns at Haynie and across assemblages in the Crow Canyon Research Database. Taxonomic diversity showed that the Haynie archaeofaunal assemblage is not significantly diverse compared to other sites, but that it is likely the most diverse faunal assemblage in the Crow Canyon database. If the rate of accumulation for new identification types continues, then it is possible the Haynie site could be one of the most diverse faunal assemblages in the central Mesa Verde region. Continued sampling will help clarify this possibility. Zooarchaeology is a crucial component of the Northern Chaco Outliers Project and will continue to provide exciting information to the archaeology of human-environment interaction in the U.S. Southwest and beyond.

7 Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mac Marston, Susan Ryan, Dave Satterwhite, and Catherine West for helpful comments and edits on previous drafts of this report. Many continued thanks to Steve Wolverton for his zooarchaeological support and inspiration.

8 References

Citation

@incollection{dombrosky2024,

author = {Dombrosky, Jonathan and Feldstein, Ahna},

editor = {David Satterwhite, R. and C. Ryan, Susan and Throgmorton,

Kellam and Copeland, Steve and Hughes, Kate and Merewether, Jamie

and Sinensky, Reuven},

title = {Year {Two} of {Archaeofaunal} {Analysis} at the {Haynie}

{Site} {(5MT1905)}},

booktitle = {Excavation and Additional Studies at The Haynie Site

(5MT1905) by Crow Canyon Archaeological Center Annual Progress

Report 2023},

pages = {70-104},

date = {2024},

url = {https://crowcanyon.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/NCOP-Annual-Report-2023_-Final.pdf},

langid = {en}

}